What is the value of power tower of square root of 2?

A simple charming puzzle that shows why rigor is required in mathematics

1. Problem Statement

I found this little innocent puzzle in one of the videos of 3b1b youtube channel1. The problem goes as follows, consider the following equation, solve for x.

\[\begin{align*} \Large{x^{x^{x^{x^{x^\text{...}}}}}} &= 2 \end{align*}\]Note: The chain is read from top to bottom, not the other way around. For example \(3^{(3^3)} = 3^{27}\), which is a ridiculously large number, however \((3^3)^3 = 27^3\) is but a infant in comparison.

One usually procedes in situtation like this as follows - Substitute the chain which as it is converging doesn’t effect if we ignore “one” power of x with “2” and solve, i.e.

\[\begin{align*} x^2 &= 2 \\ x &= \sqrt{2} \end{align*}\]We ignored \(-\sqrt{2}\) as taking of root a negative lends itself to complex domain. Now a similar question, this time you have to do it. Solve for x -

\[\begin{align*} \Large{x^{x^{x^{x^{x^\text{...}}}}}} &= 4 \end{align*}\]Is this is not our friend \(\sqrt{2}\) again!

The question is simply this, what is the value of power tower of \(\sqrt{2}\) and where was the mistake in our reasoning above?

\[\begin{align*} \large{\sqrt{2}^{\sqrt{2}^{\sqrt{2}^{\sqrt{2}^{\sqrt{2}^\text{...}}}}}} = ? \end{align*}\]2. Solution

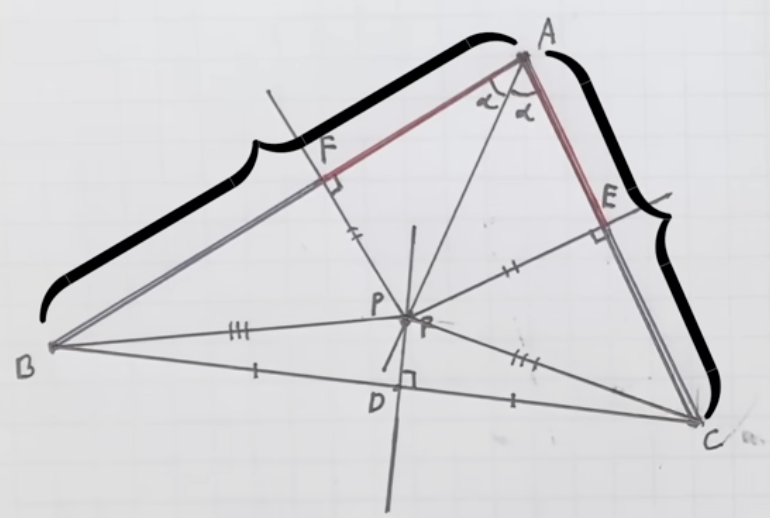

First of all, where is the fault in our reasoning? Its to do with preassumption and then not verifing if our conditions were met to begin with. This is a very common occurence in everyday mathematics, but one that manifests here as profound (?). Consider trivial example like \(x / (x-2) = 3\), or \(\sqrt{x + 4} = x - 2\). In the former, on solving we get \(x = 2\), but one must note that we assumed (while multiplying \(x-2\) on both sides) that it can’t be zero (as 0/0 != 1). Hence a verification is needed. Similarly in the later example, upon squaring and solving, we get 2 solutions, namely 0 and 5. But the former doesn’t satisfy base equation as upon squaring the negative is lost. There are many such examples, albeit not so obvious; the current one might be put in this category, where we procede under some assumptions and hence upon completion one must come back and verify that the steps were indeed allowed. Another nice example that comes to mind is, stolen shamelessly from 3b1b2 again, the proof that all triangles are equilateral. Consider a general trianble ABC. Let D be the midpoint of BC, draw a perpendicular to BC at D. Now draw the angle bisector of \(\angle A\), let P be the point of intersection with perpendicular line bisector of BC. Finally draw perpendicular to AB and AC from point P, label them F and E. The construction is shown below -

Source: 3b1b video - How to lie with visual proof

Source: 3b1b video - How to lie with visual proof

Given the following triangle congruences:

\[\begin{align*} \triangle AFP \cong \triangle AEP \text{ (by SAA)} \\ \triangle BPD \cong \triangle CPD \text{ (by SAS)} \\ \triangle BPF \cong \triangle CPE \text{ (by SSA)} \\ \end{align*}\]This leads to:

\[\begin{align*} AF = AE \text{ (from congruence 1)} \\ FB = EC \text{ (from congruence 3)} \\ \end{align*}\]Therefore AF + FB = AE + EC, which implies AB = AC. As we assume no particular significance to BC to prove AB = AC, by similar reasoning starting from AB we can show AC = BC, and hence an equilateral triangle.

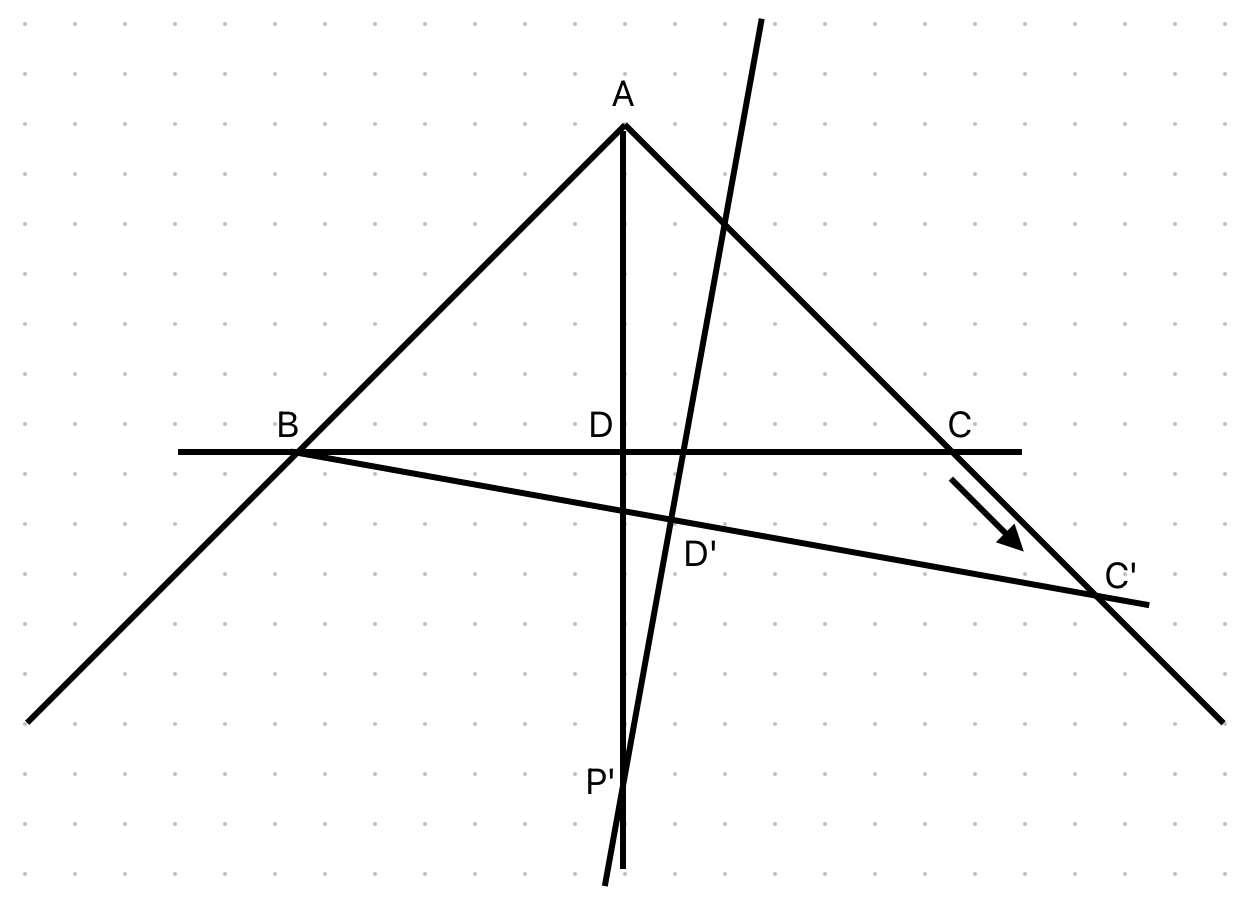

Where is the falacy? In the assumption that P lies inside the triangle! One can intuitively see that for non-isoceles triangle P will lie outside. Think of AB and AC as equal sides, and treat BC like a horizontal line. P is same as D (and angle bisector line is the perpendicular bisector of BC) in isoceles triangle. If you now start dropping C, midpoint also drops. As a result perpendicular now is forward slanting. A quick diagram shows intersection point lies outside. As all triangles can be constructed from such an arragement (think, quite geometrical, say ABC be a general triangle, Draw BC’; a horizontal line that creates ABC’ as isoceles triangle. Now ABC is acheived via our dropping of C), this proves in general.

Construction Falacy, P lies outside the triangle ABC

Construction Falacy, P lies outside the triangle ABC

Coming back to our original problem, what falacy are we making? It is sublte, and has to do with convergence. We can write our problem as \(\lim_{n \rightarrow \infty} a_n = 2\), where \(a_n\) is defined resurcively as follows: \(a_n = x^{a_{n-1}}\) and \(a_0 = 1\)3. In our reasoning when we substitute power tower of \(x\) with 2 (or 4), we are making an assumption, namely that there exist an \(x\) for which limit exist and is equal to 2 (or 4). One has to verify the validility of this step. The way one should go about the problem is, I don’t know whether such an \(x\) exist let alone find its value. But say if it does exist, (upon computation), then it can’t be anything but \(\sqrt{2}\). Let me know verify in hindsight, if with solution in mind, I could write the proof. One does a similar thing in almost every convergence proof. One doesn’t get to the limit, one assumes apriori (by “rough” methods, intution, etc) the limit which we think is true, and try to show it is indeed the limit by those epsilon proofs. Similarly here, we get a apriori solution \(\sqrt{2}\). Say similary magically we know it converges to 2, than we write a clean proof to show limit of power tower of \(\sqrt{2}\) is 2. As for the 4 case, we will show no such \(x\) exists. This is the most clean way to verify the proof, mathematically atleast we are done. How you got that is not strictly relevant. This avoids these messy and sometimes hard to spot assumptions. This is a very interesting philosophical approach and one should ponder on its subtleties.

So finally, how to show limit of power tower of \(\sqrt{2}\) is indeed 2 and no solution exists for the 4 case. We will use the idea of cobweb graph.

Let us take a detour from our proceedings, and see what this technique is. Its a visualization technique for iterative processes. For example consider a general problem: \(a_n = f(a_{n-1})\), we can ask the following questions -

- Does \(a_n\) converge? Does it happen for all initial conditions (\(a_0\))? Does it converge to the same point? If not, what are the possible end states?

- Does it cycle? If yes, whats the period.

- What is the set of points the iterate can reach?

- Something general like what is “trajectory”?

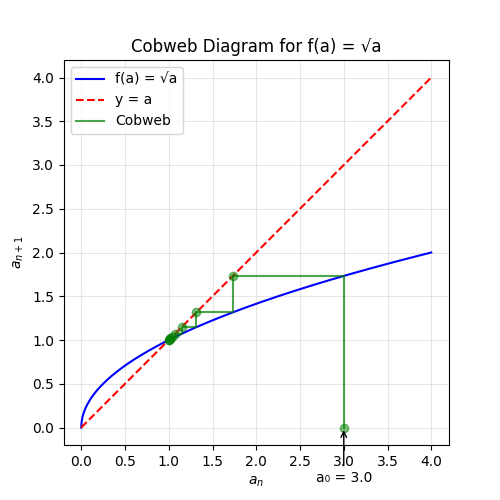

There are many techniques that are equipped to tackle these problems (like invariance principle, and the entirety of dynamic system). Cobweb4 is one amongst the plethora of them. Consider \(a_n = \sqrt{a_{n-1}}\). The technique goes as follows - Draw \(f: R \rightarrow R\) (the iterative map of \(a\)), and \(y = x\) line. Now start at \((a_0, f(a_0))\) point. Go horizontally, i.e. keeping \(y\) same, and mark the point of crossing with \(y = a\) line. From that point, reach up (or down), keeping \(a\) same and mark the point where you cross \(f\). This points’ x-coordinate is \(a_1\). We leave the reasoning to the reader, a simple calculation will convince our readers of the validity of our statement. We repeat the same process and get \(a_2\), \(a_3\) and so on. The cobweb graph for the square root function is shown below. Just remember, start from \((a_0, f(a_0))\) - first go horizontal to \(y = x\) line and then vertical to \(f\) again to get next iterate, \((f(a_0), f(f(a_0)))\).

A simple plot by hand will also get the job done. We can clearly see and convince ourselves that the web is closing in on the point of intersection of \(y=a\) and \(y = f(a)\). Which is nothing but \(a = 1\). So we can geometrical show that limit exist and is equal to 1! We can also see easily for all initial conditions, the web converges to 1! Do make a note that the graph for value < 1 is slightly different from those > 1. Now we can, if possible, write a cleaner proof for the limit by the epsilon definition. We leave the details to our enthusiastic reader5.

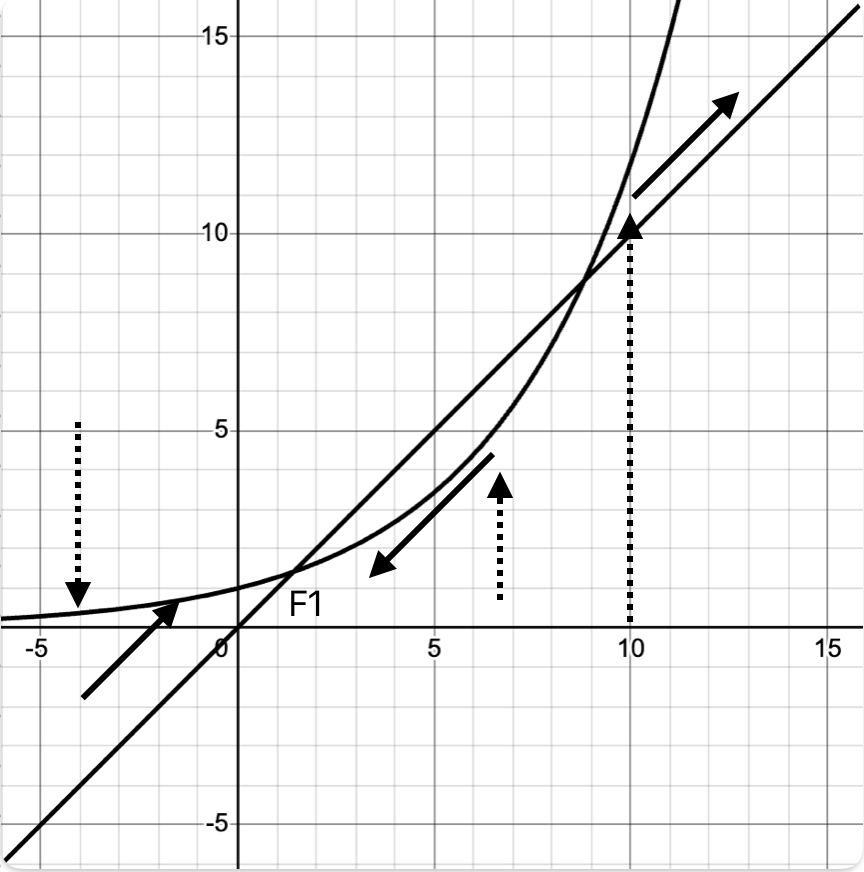

Back to our original problem, here the map is nothing but \(f(a) = x^a\) for some \(x\). We only care about \(x = \sqrt{2}\), so our reduced map is \(f(a) = \sqrt{2}^a\), with initial condition being 1. To understand the pecularity at \(\sqrt{2}\), like before, we try to follow the web. As the web behaves differently after each intersection point, we first make note of the point of intersections, below plot conveys this idea. These are also the fixed point (as \(f(a) = a\), all successive iterate remain the same). It might be that the iterate converges to the (one of the) fixed point. This is a rather deep idea, but for another day6.

Movement of Cobweb Diagram towards fixed point for x^a

Movement of Cobweb Diagram towards fixed point for x^a

Finding explicit solution for the equation \(x^a = a\) isn’t easy, however we only care about rough shape of the graph. And for that we seldom need such precise informations. A fact, anyone who has taken a course in calculus can attest a to. For \(x\) = 1, we see there is only one intersection point, and for large \(x\) no solution. As the transition has to be smooth, slightly increasing \(x\) from 1 would allow for 2 intersection points. We find the the movement when there is only one intersection point from 2, namely:

\[\begin{align*} x^a &= a \\ x^a \ln{x} &= 1 \\ \end{align*}\]Where first equation is intersection condition, and second condition is tangential condition for the unique intersection point. Solving for corresponding \(a\) and \(x\) we get: \(a = e\) and \(x = e^{\frac{1}{e}}\). It happens that \(\sqrt{2} \lt e^{\frac{1}{e}}\), and our starting point \(a_0 = 1\) lie on left side of the fixed point for the map, \(f(a) = \sqrt{2}^a\), namely \(a = 2\). And just like in shown in above figure, the web moves towards the fixed poing (F1).

The reason for failure at 4 is simple, the largest fixed point is \(e\)7 which is < 4, and as such for \(x = 4\), the web diverges. And no \(a\) exists for which converges takes place (though we only care about \(a_0 = 1\)).

Note: Our analysis breaks down when \(x \lt 1\), as the graph dynamics (web) is significantly different. Though the idea will still apply. Refer to any standard work in dynamic systems for fixed point stability analysis.

3. References

We can now make our “trick” rigorous. Suppose the \(\lim_{n \rightarrow \infty} a_n = L\). Now this is equivalent to the identity \(\lim_{n \rightarrow \infty} x^{a_{n-1}} = L\). We can move the limit inside only if limit of \(a_n\) exists. Note that we cannot write the recursion as \(a_n = a_{n-1}^x\), refer to the note in the beginning, though if we could the limit would go simply go inside instead. Here \(x\) is just a placeholder for some value, not a variable per sai. Continuing our simplication, we can move the limit inside, supposing the limit exists, \(x^{\lim_{n \rightarrow \infty} a_{n-1}} = L\), which is nothing but \(x^L = L\). I.e. if limit exist, this identity is true. Do whatever with it! Heeding the advice we try to solve for \(x\), as we know the limit. Here a simple example which shows why blind computation is simply wrong. Consider \(x + x + x + \dots = 2\), solve for \(x\). We write \(x + 2 = 2\), and proclaim \(x = 0\). Which is clearly wrong. It is not the fact that this is wrong: \(\lim a_n = L\) \(\implies\) \(\lim (x + a_{n-1}) = L\) \(\implies x + L = L\), its just that the last step is only allowed when L exist. One can see very informally the reason of failure, infinity arithmatic is not same as real airthmatic. ↩︎

Check out this desmos graph for a interactive plot of cobweb. Note that there x-axis labeled as x and not a as we are doing. And there a is our x. Please don’t confuse it. ↩︎

The corresponding \(N\) in terms of epsilon is \(N = \left\lceil \log_2\left(\frac{\ln(3)}{\ln(1 + \epsilon)}\right) \right\rceil\). Looks complex, but is rather simple calculation. One can write \(a_n = a_0^{1/2^n}\), rest follows from there. ↩︎

In the diagram, we forget to mention the point F2 (place it mentally at the right position). Note that F2 is not reached by any cobweb, and as such, F2 is not considered as candidate for 4. If web converged to it, we would have to consider 2 intersection point condition in hope that 2nd intersection point is = 4. ↩︎