PCA (Principle Component Analysis)

In this post we derive the famous PCA result and see its applications to MNIST dataset.

1. Introduction

PCA (Principle Component Analysis) is a technique for dimensionality reduction or put mathematically finding lower dimensional subspaces s.t projection of vectors onto it retain maximum “self” (like minimizing mean square error). To define our problem statement, let \(V\) be the original vector space and \(U\) be the output vector space (of lower dimension i.e.). The idea is we have points in \(V\) space, hopefully correlated in some manner1, and we would like to transform (project) them onto vectors of \(U\) space (i.e. of lower dimension) s.t that correlation is preserved. A simple way to envision it is images (which are nothing but high dimensional vectors in euclidean space). Images of the same objects (like the digit 7) hold some specific region in the vector space, our task while transforming to lower dimensional space would be to - keep the close by vectors close and far off vectors far off, i.e. preserve neighbourhood and have the ability to reconstruct original vectors2.

2. PCA

A very simple transformation that preserves locality is a Linear transform. Elementary algebra will tell this is equivalent to multiplying vectors in \(V\) by some matrix \(A\) of dimension \(u \times v\), where \(v\) and \(u\) are dimensions of input and output vectors spaces. Now let us focus on the reconstruction part. Basically given an output vector \(z \in U\) we would like to get back the original \(x \in V\) with the least error. I.e. \(\min_{W, z} \mathbb{E}[\Vert x - Wz \Vert]\)3, expectation is over all values of \(x\). This is a 2 fold optimization, we will first find the \(z\) given the reconstruction matrix \(W\) (for which we can just care about the subproblem \(\Vert x - Wz \Vert\) not the whole expectation) and then find the best \(W\).

A simpler way to arrive at same optimization problem is as follows - Imagine some points spread in 2D space. We want to find the best fit line4. A best fit line, here, is nothing but a line (out of all possible lines) that minimizes sum of difference in original vector minus the projected vector (onto the line). Here instead of 2D space, we have \(v\) dimensional vector space, and instead of a line we have its natural successor the \(u\) dimensional hyperplane. A hyperplane is equivalent to an matrix \(W\) whose column span is that hyperplane. Now we will construct our problem similar to best fit, \(\mathbb{E}[\Vert x - \text{Proj}_W(x)\Vert]\), where \(\text{Proj}_W\) is a function that takes the vector from the original vector space and returns projected vector onto that hyperplane. If one thinks, the projection is nothing but the point closest to \(x\) in the column space of \(W\), and let \(Wz = \text{Proj}_W(x)\) (as the projection lie on column space of \(W\) by definition we can write it as \(Wz\) for some \(z\) belonging in \(R^u\)). This implies \(z\) s.t it is the minima of \(\Vert x - Wz \Vert\). Which we calculate in the next section, similar to our previous formulation.

Before we proceed with the solution, we would like to mention that the problem can be simplified massively by understanding the symmetries involved in \(W\) using 2nd formulation. The hyperplane is equivalent, in so far as the column span is concerned, with infinitely many matrices (for there is no shortage of basis vectors). However the \(\text{Proj}_W(x)\) will be the same for all! This is quite intutive and also proven easily5. As a result we can pick a nicer variant of \(W\) like an orthonormal (i.e. one whose columns vectors (basis) are orthogonal and of length 1). Though we don’t use this simplication till late for no reason other than trying our hands on some algebra.

\(z\) is simple to find, one uses matrix calculus identities6 and sets the derivative to 07. We get \(z = (W^TW)^{-1}W^Tx\). To procede with \(W\), we first note a simple identity \(\min E[\Vert x \Vert]\) is equivalent to \(\min E[x^Tx]\) and also equivalent to \(\min E[\text{Tr}(xx^T)]\)8. To simplify notation we write \(z = W^+ x\), where \(W^+\) is the Moore-Penrose Pseudoinverse of \(W\). The equation \(\min \mathbb{E}[\Vert x - WW^+x \Vert]\) can be simplified as follows -

\[\begin{align*} &= \min \mathbb{E}[\text{Tr}((x - WW^+x)(x - WW^+x)^T)] \\ &= \min \mathbb{E}[\text{Tr}((x - WW^+x)(x^T - x^TW^{+^T}W^T))] \\ &= \min \mathbb{E}[\text{Tr}(xx^T - xx^TW^{+^T}W^T - WW^+xx^T + WW^+xx^TW^{+^T}W^T)] \\ &= \min \text{Tr}(\mathbb{E}[(xx^T - xx^TW^{+^T}W^T - WW^+xx^T + WW^+xx^TW^{+^T}W^T]) \\ &= \min \text{Tr}(\Sigma) - \text{Tr}(\Sigma W^{+^T}W^T) - \text{Tr}(WW^+\Sigma) + \text{Tr}(WW^+\Sigma W^{+^T}W^T) \\ &= \min - \text{Tr}(\Sigma W^{+^T}W^T) - \text{Tr}(WW^+\Sigma) + \text{Tr}(WW^+\Sigma W^{+^T}W^T) \\ \end{align*}\]Here \(\mathbb{E}[xx^T] = \Sigma\). Let me explain the little trickeries step by step. First 3 steps are algebra. In the 4th step, we make note that Expectation and trace are interchangable for a matrix9. In step 5, we use lineraity of expectation and identities like: \(\mathbb{E}[AXC] = A\mathbb{E}[X]C\)10. We also replaced the expectation of \(xx^T\) by \(\Sigma\), which represents the covariance matrix + \(\mu\mu^T\)11. While applying PCA we usually make sure that image are all aligned and centered correctly12, i.e. assume means are 0, so \(\Sigma\) is just the covariance matrix. In step 6, we removed the constant term as it doesn’t afect the minimizing problem.

Now we will exploit the properties of Moore-Penrose Pseudoinverse, or to assume no prior knowledge, of the matrix \((W^TW)^{-1}W^T\), basically we will show that the matrix, \(WW^+\), is an orthogonal projection13 which means it is both idempotent and symmetric. Let us start with idempotence, \((WW^+)^2 = WW^+WW^+ = WW^+\) because \(WW^+W = W\), which follows trivially from definition of \(W^+\). Symmetric is no different, just take the transpose and remember the 2 properties of matrix transpose: \((AB)^T = B^TA^T\) and \(A^{-1^T} = A^{T^{-1}}\)14. One more thing, trace is invariant under cyclic permutation i.e. for 3 matrices it would mean: \(\text{Tr}(ABC) = \text{Tr}(CAB) = \text{Tr}(BCA)\)15. For notation sake let us denote the projection matrix \(WW^+\) by \(P\). Above equation becomes -

\[\begin{align*} &= \min - \text{Tr}(\Sigma P) - \text{Tr}(P \Sigma) + \text{Tr}(P \Sigma P) \\ &= \min - \text{Tr}(P \Sigma) - \text{Tr}(P \Sigma) + \text{Tr}(P^2 \Sigma) \\ &= \min - \text{Tr}(P \Sigma) \\ \end{align*}\]In the last step we use the idempotent property of projection. Following our observation at the very start, that we can replace \(W\) by a orthonormal matrix, we here replace \(W\) by \(W^\prime\) (an orthonormal matrix). For an orthonormal matrix \((W^\prime)^TW^\prime = I\). Thus our final equation becomes \(\min -\text{Tr}[(W^\prime)^T \Lambda W^\prime]\). It is almost over, we would call upon the literature of Linear Algebre one last time: Eigenvalue decomposition theorem tells us that for a real symmetric matrix we have the following decomposition \(A = Q\Lambda Q^T\), where \(Q\) is the orthogonal matrix of eigenvectors (each column is the eigenvector) and \(\Lambda\) is a diagonal matrix whose entries are eigenvalues (\(\lambda_1 \gt \lambda_2 \dots \gt \lambda_n\), i.e. top to bottom in decreasing order of eigenvalues). Note that eigenvectors in \(Q\) are also in order of the eigenvalues (corresponding to them i.e.). In our problem \(\Sigma\) is a real symmetric matrix and thus posits this eigenvalue decomposition. Now as these orthogonal eigenvectors form a basis, we can write each column in \(W\) as some linear combination of them. In matrix form that would mean \(W = QY\) where \(Y\) is a \(v \times u\) matrix. Substituting above and noting that \(Q^TQ = I\) (for orthogonal matrix, it’s transpose is also it’s inverse), we get:

\[\begin{align*} &= \min -\text{Tr}[Y^T \Lambda Y] \end{align*}\]This we will solve from first principles. To get insight into solution, let us start with \(u = 1\), our problem becomes \(\min -\text{Tr}[y^T \Lambda y]\), where \(y\) is a column vector \(v \times 1\). This is equal to \(\sum_i \lambda_i y_i^2\), where \(y_i\) is the \(i\)th co-ordinate in column vector \(y\). We know \(\sum y_i^2 = 1\)16, and as \(\lambda_i\)’s are in decreasing order of \(i\), this is minimized for \(y_1 = 1\) and \(y_i = 0 \ \forall i \ne 0\). This gives \(W = Qy = v_1\), where \(v_1\) is the eigenvector corresponding to \(\lambda_1\) for the matrix \(\Sigma\). For \(u=2\) case we see that we get \(-\sum \lambda_i (y_{i1}^2 + y_{i2}^2)\), which is equal to \(-(\lambda_1 + \lambda2)\) under the constraint that both columns vectors in \(Y\) are orthogonal17. As there are many solution (each representing some combination of top \(k\) orthonormal vectors, which are themselves orthonormal), we pick the canonical, which implies \(y_{22} = 1\) and \(y_{i2} = 0 \ \forall i \ne 2\). Similarly one can show that \(W = [v_1 v_2 \dots v_u]\), where \(v_i\) is the \(i\)th column vector of \(Q\) or eigenvector correponding to \(\lambda_i\) for \(\Sigma\).

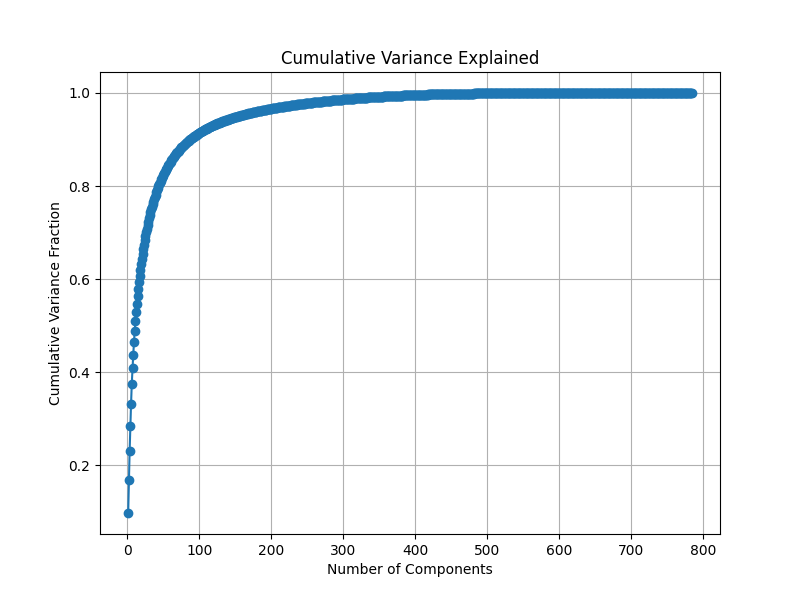

To conclude our proof, the hyperplane (from 2nd formulation) or the subspace to be projected on, is the span of eigenvectors correponding to \(k\)-largest eigenvalues. We can also quantify our result, the term we minimized was actually the variance18 and the minimum we got is \(\text{Tr}(\Sigma) - \sum_{i=0}^k \lambda_i\). This can further simplified using \(\text{Tr}(\Sigma) = \text{Tr}(\Lambda) = \sum_i \lambda_i\), which is obvious from EVD and cyclic nature of trace. We basically get variance equal to \(\sum_{i=k+1}^v \lambda_i\). Or put slightly differently amount of information preserved. Or another way of seeing is out of total variance of \(\sum \lambda_i\) (for \(k = 0\) case, i.e. projection term is 0 always), each additional dimension in reduced space removes \(\lambda_k\) variance, or brings about information worth that much. We can thus, in practice, plot this (total variance resolved vs \(k\), strictly monotonic increasing) and see after how many dimensions, say 90% variance is resolved, and there we can project.

3. Practical

Let us apply PCA to hand written MNIST dataset. The following is a python implementation our ideas.

In the code implementation \(X\) is a matrix with row vectors as our \(x\), and so is \(W\) matrix. And accordingly the projected vector is \(XW\) (for orthonormal \(Q^TQ = I\)).

First we import desired libraries -

1

2

3

4

import os

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from sklearn.datasets import fetch_openml

Step 1: Download MNIST dataset using scikit-learn and store in /Dataset folder. We write a method called download_and_save_mnist that takes in path as the input. It checks if the path exist, if not it creates it, and download mnist dataset from sklearn’s repository.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

def download_and_save_mnist(dataset_dir='./Dataset'):

if not os.path.exists(dataset_dir):

os.makedirs(dataset_dir)

# Fetch MNIST from OpenML

mnist = fetch_openml('mnist_784', version=1, as_frame=False)

X = mnist['data']

y = mnist['target']

# MNIST on OpenML provides 70,000 samples, we can split into training and test sets:

x_train, x_test = X[:60000], X[60000:]

y_train, y_test = y[:60000], y[60000:]

# Save as numpy arrays for later use

np.save(os.path.join(dataset_dir, 'x_train.npy'), x_train)

np.save(os.path.join(dataset_dir, 'y_train.npy'), y_train)

np.save(os.path.join(dataset_dir, 'x_test.npy'), x_test)

np.save(os.path.join(dataset_dir, 'y_test.npy'), y_test)

print(f"MNIST data saved to {dataset_dir}")

Step 2 & 3: PCA class definition. The API interface we follow is as follows: We have a PCA object that on init takes the input cluster of vectors. Internally it finds and stores the eigenvalues and eigenvectors. It also calculates the mean and normalizes the vectors. The same normalization will be done on all vectors wanting to be transformed. Afterwards it provides the main api, transform(), it takes a vector (or a batch of them), and reduced dimension as the input and outputs the transformed (reduced-dimensional) vector(s). Finally we added a method to plot the resolved variance for quick accessibility. Note that this method is independent of what dataset you use, all that is encoded inside the input vectors X.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

class PCA:

def __init__(self, X):

"""

Initialize with input vectors.

X should be a np.array([m,n], dtype=np.float64), where m is number of samples.

Computes eigenvalues and eigenvectors of E[X^TX] (covariance matrix).

The computed eigenvalues and eigenvectors are stored in:

self.eigenvalues : np.array sorted in descending order

self.eigenvectors: corresponding eigenvectors as columns.

"""

# Ensure X is float and (if necessary) flatten images.

self.X = np.array(X, dtype=np.float64)

# Center the data

self.mean = np.mean(self.X, axis=0)

X_centered = self.X - self.mean

# Compute covariance matrix: (1/m) * X_centered^T * X_centered

cov_matrix = np.dot(X_centered.T, X_centered) / X_centered.shape[0]

# Compute eigenvalues and eigenvectors using eigh (symmetric matrix)

eigenvalues, eigenvectors = np.linalg.eigh(cov_matrix)

# Sort eigenvalues and eigenvectors in descending order.

idx = np.argsort(eigenvalues)[::-1]

self.eigenvalues = eigenvalues[idx]

self.eigenvectors = eigenvectors[:, idx]

def transform(self, input_vectors, n_components):

"""

Project input_vectors onto the top n_components eigenvectors.

input_vectors: np.array of shape (m, n) or (n,) for a single sample.

Returns a np.array of shape (m, n_components) or (n_components,) for a single sample.

"""

# Ensure input_vectors is 2D.

single_sample = False

if input_vectors.ndim == 1:

single_sample = True

input_vectors = input_vectors.reshape(1, -1)

# Center the input vectors using the training mean.

input_centered = input_vectors - self.mean

# Project using the top n_components eigenvectors.

projection_matrix = self.eigenvectors[:, :n_components]

transformed = np.dot(input_centered, projection_matrix)

if single_sample:

return transformed.flatten()

return transformed

# Step 4: Function to plot cumulative variance plot.

def plot_cumulative_variance(self):

"""

Plots cumulative variance explained by the eigenvalues.

x-axis: number of components, y-axis: cumulative fraction of variance.

"""

total_variance = np.sum(self.eigenvalues)

cumulative_variance = np.cumsum(self.eigenvalues) / total_variance

plt.figure(figsize=(8,6))

plt.plot(range(1, len(self.eigenvalues) + 1), cumulative_variance, marker='o', linestyle='-')

plt.xlabel("Number of Components")

plt.ylabel("Cumulative Variance Fraction")

plt.title("Cumulative Variance Explained")

plt.grid(True)

plt.show()

Step 5: Function to plot 2d inputs with labels. This is just a helper function to see the projection on 2D hyperplane.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

def plot_2d_projection(data, labels):

"""

Plots 2D data points with different colors for each label (0-9).

data: np.array of shape (m, 2)

labels: np.array of shape (m,)

"""

plt.figure(figsize=(8,6))

unique_labels = np.unique(labels)

for label in unique_labels:

idx = labels == label

plt.scatter(data[idx, 0], data[idx, 1], label=str(label), alpha=0.6)

plt.xlabel("Component 1")

plt.ylabel("Component 2")

plt.title("2D Projection of MNIST Data")

plt.legend(title="Digit")

plt.grid(True)

plt.show()

Step 6: Example usage. Finally we provide an executable code snippet.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

if __name__ == "__main__":

# Download and save dataset using OpenML

download_and_save_mnist()

# Load data from saved files. For PCA, we often use the training set.

dataset_dir = './Dataset'

x_train = np.load(os.path.join(dataset_dir, 'x_train.npy'), allow_pickle=True)

y_train = np.load(os.path.join(dataset_dir, 'y_train.npy'), allow_pickle=True)

# Create PCA instance using the training data.

pca = PCA(x_train)

# Plot cumulative variance explained.

pca.plot_cumulative_variance()

# Reduce the dimension to 2 for visualization.

x_train_2d = pca.transform(x_train, 2)

# Plot the 2D projection with corresponding labels.

plot_2d_projection(x_train_2d, y_train)

Cummulative resolved Variance plot. Around 100 eigenvectors provides 90% of the variance.

Cummulative resolved Variance plot. Around 100 eigenvectors provides 90% of the variance.

PCA is quite useful apart from size reduction too. An image (like the handwritten dataset above) often has many superficial dimensions. Like all that white pixels around the digit, or like pixels correponding to elements of image that are common throughout the dataset and as such aren’t special to it. For machine learning tasks like classification, this extra information makes it a hard learning problem in 2 ways - curse of dimensionality, training on information that is not relevant. Curse of dimensionality refers to the idea that when we increase dimension, the amount of information required to make the same caliber of prediction like in classification tasks, increases exponentialy19. And exponential is not something that is feasible, even for our low resolution images the dimensionality is 784. Thus applying learning algorithms on transformed dataset, which is void of such superfuluous details, is desired.

Notes

Mathematically correlation (Pearson’s) refer to \(\rho_{X,Y} = \text{Cov}(X,Y) / (\sigma_X \sigma_Y)\), where \(\text{Cov}(X,Y)\) is given by \(\mathbb{E}[(X-\mathbb{E}[X])(Y - \mathbb{E}[Y])]\). The idea is very simple: If \(X\) and \(Y\) are independent this term is 0, which is clear from property of expectation as well as the intutive idea that on average \(X\) (mean subtracted, same goes from all references of \(X\) and \(Y\) in this note) is as much positive as negative for same \(Y\) resulting in net 0 contribution. When they are not independent, a positive covariance would represent that when \(X\) is positive, on average \(Y\) tends to be positive too (and similarly both negative). And negative covariance would mean when \(X\) is positive (negative) \(Y\) on average is negative (positive). Correlation is just a normalization of this value, as covariance can be arbitarily small or large (depending on range of \(X\) and \(Y\)) the value looses quantitative significance. Correlation thus divides it by standard deviation of \(X\) and \(Y\), and it turns out \(\rho_{X,Y} \in [-1,1]\), and the boundary values are attained when \(X = (+-) Y\), i.e. perfect correlation. ↩︎

I had this doubt about compression. We know there exist a bijection between \(\mathbb{R}\) and \(\mathbb{R}^n\), albeit not neighbourhood preserving, but appears to be very space friendly. So why haven’t we heard of such a simple compression. There are many reasons, paramount of which is these bijection’s aren’t space preserving. Bijection is just a ordering, net information hasn’t decreased. Consider the example of Hilbert’s space filling curves, when they map \((a,b)\) to \(c\), on surface we saved on space of 1-coordinate, but if we look in bit size \(c\) would have to quite large. Basically bits in form of co-ordinates are being exchanged for bits of \(c\). Conceretly let both \(a\) and \(b\) be 8-bit integers, then \(c\) will have to be a 16-bit integer to hold all the values (this is finite setting). This begs the question how to compress something then (losslessly)? By exploiting repeating and patterns. For example, consider a message that has all “A” 1000 times. Instead of writing it explicitly we can encode it as “A 1000”. Hufmann algorithm is one such illustration. This is closed related to information theory, refer to Shannon’s source coding theorem . ↩︎

This is just fancy way of writing least mean square error. It is nice compact way of writing, which puts ideas of simplicity at forefront as you will see in the proof. Linearity of expectation, distribution over product, etc are much more apparent in this format compared to the expanded sum format. This is ubiquitous in modelling optimization problems. Another slightly different way of seeing, consistent with the formuluation, is by having a uniform measure over all possible \(x\)’s and minizing the mean error. ↩︎

In literature a best fit line is defined somewhat differently, albeit close. Let \(x \in \mathbb{R}^n\) be points for which value \(y \in \mathbb{R}\) is known. Our task is to find the best fit line, which is \(\text{argmin}_w E[(y_i - w^Tx_i)^2]\). Think of it in \(n = 1\), we are finding a line for which vertical gap is minimized (squared to take care of negative and positives for both are of same importance, equivalently we could have tried absolute value, it is called least absolute deviation line and \(w = \text{median}(y_i/x_i)\)). It terms out \(w = (XX^T)^{-1}XY\), the proof is quite simple; our equation is equivalent to norm of column vector \(Y - X^Tw\), where \(Y\) is column vector of values and each column in \(X\) is one of our points. Now use matrix calculus over the term \((Y-X^Tw)^T(Y - w^TX)\). ↩︎

The proof follows readily from the observation that if \(W_1\) and \(W_2\) are 2 matrices with same column span, we can write \(W_2 = W_1 A\), where \(A\) is an invertible matrix. This follows from the fact that both has same column span, or specifically each column of \(W_2\) can be expressed as linear combination of column vectors of \(W_1\) (i.e. \(v_i = W_1 u_i\) where \(v_i\) is the \(i\)th column vector of \(W_2\) and \(u_i \in \mathbb{R}^u\) is the appropriate combination of columns of \(W_1\), also the \(i\)th column of \(A\)). \(A_{u \times u}\) is invertible as each \(u_i\) is independent (because each transformation of \(u_i\) under \(W_1\) is independent). Plug it into the formula for \(\text{Proj}_W(x) = W(W^TW)^{-1}W^Tx\) and show that \(\text{Proj}_{W_1}(x) = \text{Proj}_{W_2}(x)\). ↩︎

The matrix calculus, differentiation and integration of function from multidimensional space to multidimensional space (here differentiation can be a matrix, as that would tell how much changing \(x_1\) co-ordinates in input changes \(y_1\) co-ordinates in output), identites are \(\nabla Ax = A\), \(\nabla x^TAx = x^T(A + A^T)\), and if \(x\) is some function of \(z\) then \(\nabla_{z} x^TAx = x^T (A + A^T) \nabla_z x\). For our calculation, note that minimizing norm of \(x\) is same as minimizing norm squared, which can be written as \(x^Tx\). Thus our minimization problem becomes \((x-Wz)^T(x-Wz)\), using our result we get \(2(x - Wz)^T (-W)\). Equating it to 0, we get \(z = (W^TW)^{-1}W^Tx\). Note that \(W\) doesn’t have inverse but \(W^TW\) has if it is full rank20 (which we will make sure to check once we have constructed \(W\)). One might be tempted to conclude from the equation \(W^T(x - Wz)\) that \(x - Wz = 0\), however one must note that \(W\) is not invertible so direct inverse doesn’t exist, rather one would have to take the Moore-Penrose Pseudoinverse which is nothing but the matrix, \((W^TW)^{-1}W\). ↩︎

One has to very careful while setting derivative to 0 and hoping for a local minima. Consider the simple case of \(x^TAx\) whose derivative is \(x^T(A + A^T)\), this is equal to 0 only when \(x = 0\). But multivariable calculus will tell you whether the point is local minima, maxima, saddle, or inconclusive depends on the matrix \(A\). In general, if the hessian is positive definite (all eigenvalues > 0) then it is a local minima, if negative definite then it is a local maxima and if there are eigenvalues both positive and negative it is saddle point. For positive or negative semidefinite (\(\lambda \ge \text{ , } \le 0\)), this test is inconclusive. The reasoning is not too difficult, another way of defining definitiveness of a matrix is by evaluating the function \(x^TAx\). If this function is always positive (any \(x\)), then the matrix is deemed positive definite. If \(\ge 0\) positive semidefinite, if always < 0 negative definite. If sometimes positive and sometimes negative indefinite. It can be shown our 2 definitions are equivalent. Using Taylor series we can have a 2nd degree approximation of our function, \(f(y) = f(x)\) \(+ \nabla f(x) (y-x)\) \(+ 1/2 (y-x)^T \nabla^2 f(x) (y-x)\) \(+ \mathcal{O}(\Vert y - x \Vert^3)\). For a critical point (\(x^*\) s.t \(\nabla f(x^*) = 0\)), this becomes \(f(y) = f(x^*) +\) \(1/2 (y-x^*)^T \nabla^2 f(x^*) (y - x^*)\), we ignored the higher term as for sufficiently lower \(\Vert y - x \Vert\) it becomes strictly less than our \(1/2 (y-x^*)^T \nabla^2 f(x^*) (y - x^*)\) term. By definition of positive definitiveness \(f(y) \gt f(x^*)\), as long as the higher order term can be removed i.e. nearby point only, which is all we care about. Similarly for negative definitiveness \(f(y) \lt f(x^*)\), and same for indefinite. In our case when \(f(z) = (x - Wz)^T(x - Wz)\), the \(\nabla f(z) = -2W^T(x-Wz)\) and \(\nabla^2 f(z) = 2W^TW\). If \(W\) is a full column rank, which we will make sure to check, then \(W^TW\) is positive definite, and subsequently \(z^*\) s.t \(\nabla f(z^*) = 0\) is a local minima. ↩︎

The first relation is true because minimizing \(\Vert x \Vert\) is same as minimizing \(\Vert x^2 \Vert\). And \(\Vert x^2 \Vert\) is square of L2 norm and is equivalent to \(x^Tx\). The last relation when expanded out is also squared L2 norm. ↩︎

Before we explain why, let us first define \(\mathbb{E}[A]\) where \(A\) is a matrix. This is a matrix itself \(A^\prime\) s.t each entry \(a^\prime_{ij} = \mathbb{E}[a_{ij}]\), i.e. each entry in matrix is just the expecation of that entry in input matrix. We claimed that \(\mathbb{E}[\text{Tr}(A)] = \text{Tr}(\mathbb{E}[A])\). One can simplify expand both terms and quickly realize these are the same thing. ↩︎

This is a trivial result. To build the intution, consider the term \(\mathbb{E}[AX]\), expectation is over X. The way to solve this would be to first multiply both the matrices and then take the expectation in each cell. But notice as expectation is linear and \(\mathbb{E}[ax] = a\mathbb{E}[x]\), one realizes expectation just replaces entries \(x_{ij}\) by \(\mathbb{E}[x_{ij}]\), i.e. to visualize we just changed the label \(x\) to \(\mathbb{E}[x]\) and nothing more, which would mean this is nothing but multiplication of \(A\mathbb{E}[X]\). From similar reasoning we can write \(\mathbb{E}[AXB] = A\mathbb{E}[X]B\) too. To extend our result, even this is true \(\mathbb{E}[AXBX] = A\mathbb{E}[X]B\mathbb{E}[X]\) given all the elements of \(X\) are independent (so that \(\mathbb{E}[x_1x_2] = \mathbb{E}[x_1]\mathbb{E}[x_2]\), and the label replacing logic works flawlessly). ↩︎

In our case vector \(x\)’s co-ordinates aren’t independent, else its pointless, our purpose is to exploit symmetry of alignment / preference in some particular direction, hence they are co-related. So one cannot write \(E[xx^T]\) with the off-diagonal elements simply as the product of correponding means. To make our point consistent with literature, we define covariance matrix as \(\Sigma = \mathbb{E}[(x-\mu)(x-\mu)^T]\), where \(\mu\) is a vector of same dimension s.t each co-ordinate is expectation of corresponding co-ordinate of \(x\). Here if co-ordinates of \(x\) are independent, off-diagonal elements are 0 (why?) and the diagonal elements are nothing but variance of respective co-ordinate. When the co-ordinates aren’t independent the off-diagonal terms, like say entry for (1,2) = \(\mathbb{E}[(x_1 - \mu_1)(x_2 - \mu_2)]\) is equal to \(\text{Cov}(x_1, x_2)\). ↩︎

This is not hard to do. Suppose you have vectors \(x_1, \dots , x_n\), normalize each by following operation: \(x_i \rightarrow\) \(\frac{x_i - \mathbb{E}[x] }{\sqrt{\text{Var}(x)}}\). This normalization ensures 0 mean and 1 variance. ↩︎

A projection is a linear transform s.t repeated application has no effect. This is a simple definition, once we have projected a vector onto some subspace, taking the projection again should return the same vector. I.e. \(Px = P^2x \ \forall x\), which gives us the mathematically definition of projection, \(P = P^2\) (Idempotent). Now there is another desireable property for a projection called orthogonality, which is \(\langle Px, x - Px \rangle = 0 \ \forall x\). This gives \(P^T = P^TP\). Taking transpose we get the definition for orthogonal projection (along with idempotence) \(P = P^T\). If you remember the second way of formuating our problem, we compute \(z\) s.t it is orthogonal projection. It is no suprise that this is an orthogonal projection. ↩︎

The proofs are pure algebra. For the former, let \(C = AB\), we know \(C_{ij}\) is product of \(i\)th row of \(A\) and \(j\)th column of \(B\). And \(C^T_{ij} = C_{ji}\) equals to \(j\)th row of \(A\) and \(i\)th column of \(B\). This product can be written is \(i\)th row of \(B^T\) (as \(i\)th column of \(B\) becomes \(i\)th row of \(B^T\)) and \(j\)th column of \(A^T\). By definition of matrix product, this implies \(C^T = B^TA^T\). For later, we know \(A^{-1}A = I\). Taking transpose we get \(A^T A^{-1^T} = I\), which means \(A^{-1^T}\) is the inverse of \(A^T\), i.e. \(A^{T^{-1}} = A^{-1^T}\). ↩︎

It follows immediately from the observation that for 2 matrices \(\text{Tr}(AB) = \text{Tr}(BA)\). This is quickly realized upon computation, all the term in trace are of form \(a_{ij}b_{ji}\). When we switch the order the same “transpose” term form the product, these terms can be thought of as complementary. Once we have this, we can show that \(\text{Tr}(A_1A_2 \dots A_n) = \text{Tr}(A_nA_1 \dots A_{n-1})\). Define \(M = A_1 \dots A_{n-1}\), as matrix multiplication is associative we can write our equations as \(\text{Tr}(M A_n) = \text{Tr}(A_nM)\), which we have already proved. Now using this as the starting point we can show that the same is equal to \(\text{Tr}(A_{n-1}A_n A_1 \dots A_{n-2})\), and so on for all cyclic permutations. ↩︎

Euclidean length doesn’t change length under rotation of co-ordinate system. Or put simply \(w= Qy\), take norm on both sides we see norm of \(y\) is 1. This is same as showing our earlier claim for any rotation of co-ordinates is given by an orthonormal matrix only. ↩︎

This is not too hard to see. First we should agree it is pointless to have the vector \(y\) to have non-zero entries for co-ordinates representing >2 eigenvalues. Now the only question remains what if there is a way to assign \(y\)’s s.t they are orthogonal and better than our sum. This is not possible, as a fact all values of orthonormal pairs gives same value. The reason is in \(n\)-dimensional space, a set of vectors is an orthonormal basis iff sum of each co-ordinate squared is 1! (i.e. if \(e_1, e_2, e_3\) are orthonormal basis than \(e_{1i}^2 + e_{2i}^2 + e_{3i}^2 = 1\) \(\forall i \in [1, 2, 3]\)) This is a reasonable claim, every orthogonal basis is related in some ways and this gives a quantifiable low level relation. The proof is simple too. One must understand a vector \(v\) = \((v.e_1)e_1 + (v.e_2)e_2 + (v.e_3)e_3\) iff \(e_1, e_2, e_3\) are orthonormal basis. This is just a different way of defining orthonormal vectors, and simple to see. We know as they form a basis, any vector can be written as a linear combination of these. Take inner product with each basis and find the co-efficient. Now let \(v = [1,0,0]\) and compute right hand side. You will get the first co-ordinate squared equal to 1 identity. This is easily generalized, and our final proof follows. ↩︎

If \(x\) is a column random vector with 0 mean, and \(T\) be a linear transformation then \(\mathbb{E}(T(x))\) is also 0. This is easy (atleast rigoursly for discrete case and informally for continous case) to see from the property that \(aL(x) = L(ax)\), \(a\) being a scalar. Variance, here, tells on average the length of perpendicular vector. ↩︎

This is closely related to the fact that most classification algorithms are distance based, and in higher dimension it turns out due to availability of extra dimensions, images are almost uniformly away (closest point is almost same distance away as farthest point). All these algorithms at heart are meant to capture the density of neighbourhood. We want to assign the label which is most prevelant in the neighbourhood. As such we would like to mantain same density and hence the exponential. ↩︎

A full column rank means all the column vectors are linearly independent. Let \(W\) be a full column rank matrix, then we will show that \(W^TW\) is positive definite. Positive definite means \(v^TWv \gt 0 \ \forall v\), here that would mean, \(v^T W^T W v =\) \((Wv)^T(Wv) =\) \(\Vert Wv \Vert^2\). This is clearly \(\ge 0\) and equal to 0 only when \(v = 0\) because columns of \(W\) are linearly independent. We also know that a matrix is invertible iff it is non-singular, i.e. determinant is non-zero. But determinant is just the product of all the eigenvalues. As \(W^TW\) has all positive eigenvalues (alternate definition of positive definite matrix), determinant is \(> 0\), and thus \(W^TW\) is invertible too. ↩︎

](/blog/assets/img/PCA/thumbnail.jpg)